During pregnancy, the body undergoes numerous transformations—breasts expand, resting heart rate increases, and organs shift to accommodate the growing fetus. Now, scientists have uncovered another remarkable change: the gut undergoes significant growth.

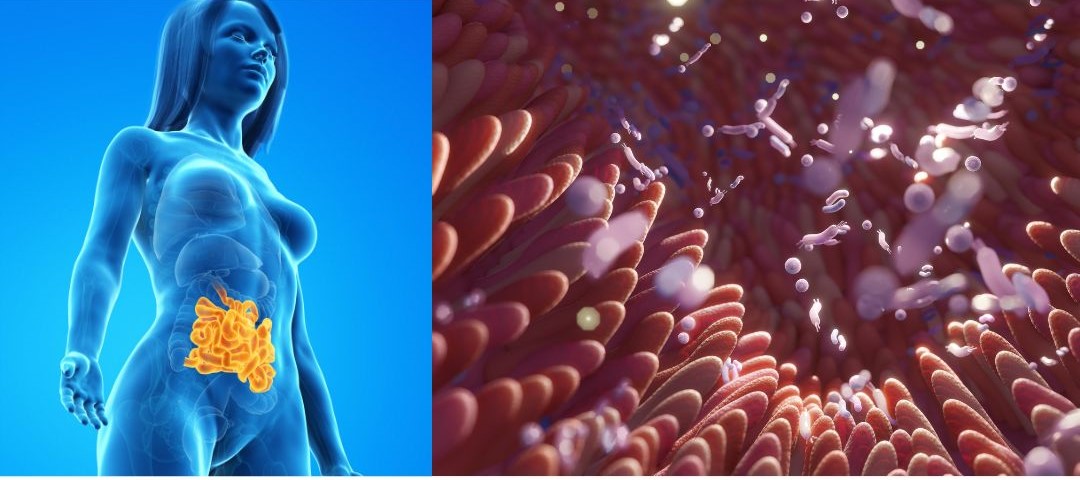

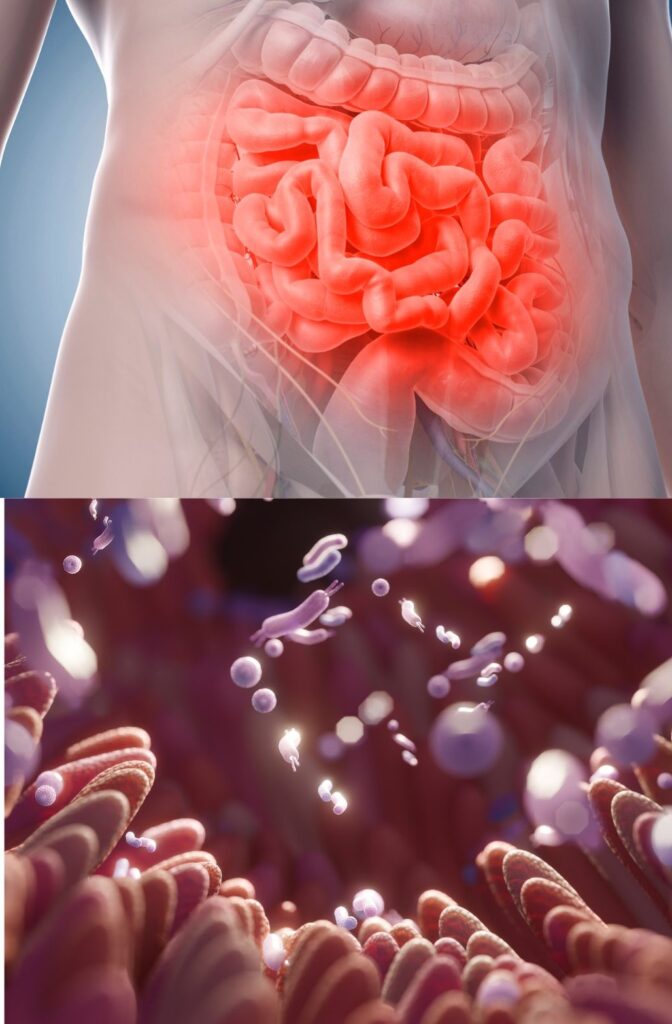

According to new research conducted on mice and 3D models of human tissue, the inner lining of the small intestine, known as the epithelium, doubles in size during pregnancy and breastfeeding. These structural changes may enhance the body’s ability to absorb nutrients, ensuring both the mother and baby receive essential nourishment.

Pregnant individuals need to consume more nutrients to support fetal development, and researchers speculate that this intestinal expansion allows for greater nutrient absorption. However, this theory is yet to be fully confirmed. “Our team has discovered an amazing new way in which the body adapts to keep babies healthy,” said Josef Penninger, scientific director at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research in Germany.

The researchers made this discovery while studying the role of a signaling molecule called RANK, which is found in various tissues throughout the body. Previously, RANK was known to regulate the formation of milk-producing mammary glands. Since hormones like progesterone increase RANK production during pregnancy, scientists suspected it might play a role in other reproductive-related changes.

In their study, Penninger and his team used stem cells to grow small 3D replicas of human and mouse small intestines, known as organoids. When they exposed these organoids to RANK, significant structural changes occurred—tiny, finger-like projections called villi, which aid in nutrient absorption, elongated and flattened. The same transformation was observed in pregnant and breastfeeding mice. However, in genetically modified mice that lacked RANK, these intestinal changes did not occur.

Further experiments revealed that the milk produced by RANK-deficient mice contained fewer nutrients, leading to underweight offspring. These findings suggest that the intestinal epithelium remodels itself during pregnancy and lactation to optimize nutrient absorption for the developing baby.

“These new studies provide, for the first time, a molecular and structural explanation of how and why the intestine adapts to the increased nutrient demand of mothers,” Penninger explained.

This discovery sheds new light on the body’s intricate adaptations during pregnancy, opening the door for further research on maternal health and fetal development.